“I Have a Dream:” What are Freedom Schools?

I love freedom schools! I love everything about them.

I wish I could have attended a freedom school. And I wish our public education system incorporated the essential aspects of freedom schools. Perhaps that’s why, in writing The FOG MACHINE, I chose to have my character twelve-year-old Joan Barnes visit the Meridian Freedom School with her physician father.

I do not know how many white children saw the inside of a freedom school in 1964 Mississippi. I certainly did not. Historical authenticity is a guiding principle in my writing. Being historically authentic means to me that events portrayed either actually happened—in that time and place, in that way—or could have happened.

There was no free clinic at the Meridian Freedom School as I have portrayed in The FOG MACHINE. However, the Medical Committee for Human Rights, the organization through which Doc Barnes volunteers, staffed a clinic in Jackson for Freedom Summer volunteers from all over Mississippi. And the Meridian Freedom School is an authentic choice for where to set a clinic because the Klan did not watch the school as they did other locations such as the COFO office or Freedom Center. Thus, Joan’s circumstances position her to spend time at the Meridian Freedom School and consider the many questions that experience presents.

What were the 1964 freedom schools?

According to a May 5, 1964, “Memorandum to Freedom School Teachers,” the schools’ purpose was “to provide an educational experience for students which will make it possible for them to challenge the myths of our society, to perceive more clearly its realities, and to find alternatives, and ultimately, new directions for action.”

When, early in 2012, I decided to expand my single-chapter treatment of Freedom Summer, making it a pivotal element of my novel, I needed to do a deep dive to understand the 1964 freedom schools. I connected with Gail Falk who heard the call to join the Mississippi Freedom Project as a junior at Radcliffe College in Cambridge, MA. She agreed to advise me.

Gail arrived in Meridian, Mississippi in late June 1964 and was assigned as a freedom school teacher at the old Baptist Seminary on 31st Street and 16th Avenue. During that summer, the school had as many as 300 students taking classes, learning about Black literature and history, biology, French, and many other subjects, as well as music and dance. When public school opened in August and students returned to their regular classes, she continued teaching at the Freedom School as an after-school and weekend program.

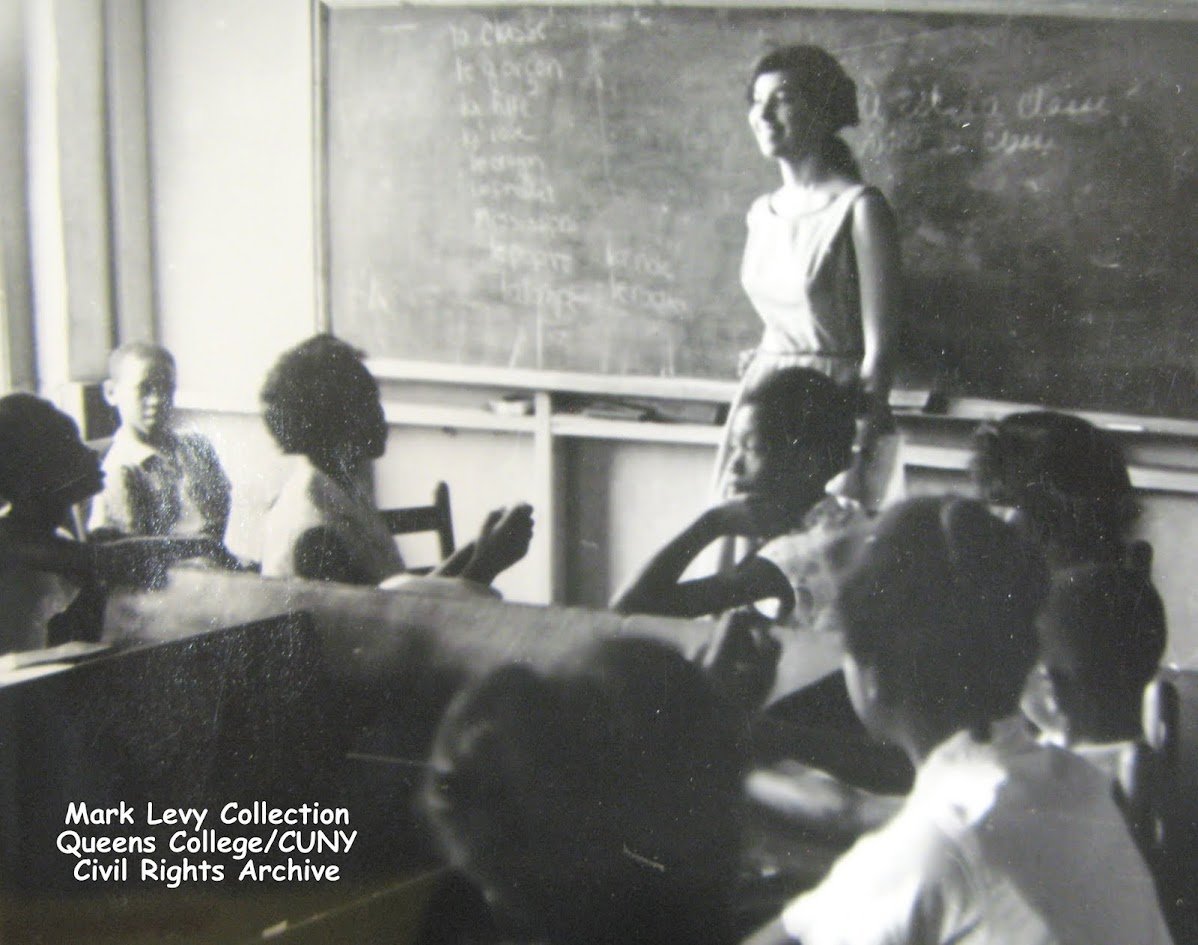

Gail Falk, teaching in the Meridian Freedom School

Courtesy Mark Levy Collection, Queens College/CUNY Civil Rights Archive

Here are some of the key things Gail told me about that summer during which teachers and students were learning together:

There was curriculum, but teachers were encouraged to improvise, and did do, in order to meet the needs of their students.

Teachers emphasized that they were not there to tell students the answers. Rather, the students had answers inside them and could think about what’s right.

Fiction was an essential resource in building both literacy and awareness. It’s often easier to contemplate a fictional character’s situation and choices because fiction allows stepping out of the here and now to view an arc in time. Books were carefully chosen so that kids saw themselves reflected. For example; The Snowy Day, by Ezra Jack Keats, for younger kids and Black Boy, by Richard Wright, for older kids.

Each of the things Gail told me maps nicely onto one or more of the principles the Freedom School curriculum was designed to serve:

The school is an agent of social change.

Students must know their own history.

The curriculum should be linked to the student’s experience.

Questions should be open-ended.

Developing academic skills is crucial.

What differentiated 1964 freedom schools?

My own K-12 experience depended far too heavily on memorization and regurgitation. If anything, that may be even more true for today’s kids. In comparison, what made the 1964 freedom schools so extraordinary was the centrality of the question.

Image by Stephan from Pixabay

Indeed, one of the key lessons taught in the 1964 freedom schools was not just the right, but the responsibility to question.

Gail Falk considered thinking of questions to be her foremost job as a freedom school teacher. Key questions all teachers asked were:

What does the majority culture have that we want? That we don’t want?

What do we have that we want to keep? Get rid of?

Howard Zinn—historian, author, professor, playwright, and activist—wrote in “Freedom Schools” in The Zinn Reader: “The kind of teaching that was done in the Freedom Schools was, despite its departure from orthodoxy—or more likely, because of it—just about the best kind there is…(The teachers) taught, not out of textbooks, but out of life, trying to link the daily headlines with the best and deepest of man’s intellectual tradition.”

Critical thinking, which relies on questioning as well as interpreting, enables us to see through the obfuscation by the fog machines in our world. I therefore believe that critical thinking skills are fundamental to the preservation of our democracy. It follows that teaching them would be one of the most important enhancements we could make to our American education system.

Freedom Summer veteran Charles Cobb calls the education received by so many African Americans and poor whites during the Freedom Summer era “sharecropper education.” When we educate with a singular focus on enabling students to perform specific roles in life—whether as sharecroppers then, or technology workers today—we shortchange the individual and society.

Are there any freedom schools today?

Absolutely! Both Mississippi’s freedom projects and the Children’s Defense Fund freedom schools share major tenets of the 1964 freedom schools. The Children’s Defense Fund Freedom Schools program, founded by Marian Wright Edelman, operates over 130 summer programs in at least 24 states. In Minnesota alone, over 137,000 pre-K-12 kids have taken part in the CDF Freedom Schools program since 1995.

Sixty years ago, Meridian was home to the largest freedom school. It was held in the historic Meridian Baptist Seminary building, a two-story brick building wonderfully equipped for a school.

In 2014, as I was launching The FOG MACHINE, the Meridian Freedom Project was launched. The MFP is a college pathway program, modeled on Sunflower County’s highly successful program. The MFP facility, though far from plush, is a comfortable one-story space with modern audio-visual capabilities. Kids at the MFP are roundly encouraged to question, just as their 1964 counterparts were. And they learn African American and civil rights history.

When I wrote about Meridian’s Freedom School, I never dreamed I might one day teach in one. Yet there I was, conducting an “I Have a Dream Writers’ Workshop” for rising sixth, seventh, and eighth graders.

Following morning meeting, which concludes with singing freedom songs, I was off to visit with each rhetoric class, where I asked students to brainstorm in response to the targeted prompt:

“I have a dream that one day…”

Brainstorming with Rhetoric Students at Meridian Freedom Project

Photo by Dani Follett-Dion

While researching The FOG MACHINE, I’d acquired compositions on the same theme by actual 1964 Meridian Freedom School students. Meridian Freedom Project students, teachers, and I then engaged in a rare opportunity to compare and contrast viewpoints of students during Freedom Summer and fifty years later!

Similarities were both heartening and sad. Like their 1964 counterparts, 2014 students had great aspirations. Inspired by their mayor, Meridian’s first African American to hold that office, several hoped to one day follow him. Girls had expanded their reach since 1964, with multiple students hoping to go into medicine, especially to serve the homeless population. Kids in both 1964 and 2014 appreciated the value of education.

Although problems the 2014 students dreamed of eliminating took on modern-day shapes, there were eerie similarities. Kids during both Freedom Summer and the summer of its 50th anniversary worried a great deal about safety, theirs and their family members’. Seemingly gone in 2014 was the fear of being terrorized as a race. In its place was the fear of rising violence in response to economic inequality, and bullying based on anything from gender preference to the clothes they wear.

Even as kids in both groups dreamed of race becoming a non-issue, 2014’s kids were troubled by its persistence. While 1964 students imagined the first Black US President, a 2014 dream was about the first woman President.

What might the future hold?

In Freedom Summer and the Freedom Schools (2004), Kathy Emery, Sylvia Braselmann, and Linda Gold ask:

“Are schools servants of the existing social system, no matter how unjust that system might be, and is the task of teachers to modify student aspiration to ensure their students a place in the world as it is?”

“Or is the classroom a place for transformation?”

Emery, Braselmann, and Gold further cite questions raised by Howard Zinn in 1964 as he compared our American education system to the freedom schools. Zinn wondered:

If we might accept “as an educational goal that we want better human beings in the rising generation than we had in the last.”

And if we might “declare boldly that the aim of the schools is to find solutions for poverty, for injustice, for race and national hatred, and to turn all educational efforts into a national striving for those solutions.”

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Lyon, Danny.

"Come Let Us Build a New World Together" poster, 1963. Retrieved from the Digital Public Library of America, http://cdm16118.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p16118coll37/id/1087. (Accessed July 29, 2024.)

Pause for a moment. Just imagine what that would be like!

Freedom Summer’s 1964 freedom schools showed what’s possible in relation to these questions. Present-day freedom schools of the Mississippi Freedom Projects and Children’s Defense Fund continue to show what’s possible.

I have a dream that one day…our American education system might pick up the mantle and follow their lead.

Thanks for reading this Stories from Civil Rights History, Then and Now BLOG post by author Susan Follett.

Please let me know what you think!

Copyright (C) 2024 Susan Follett. All rights reserved.