Photo by Dani Follett-Dion

ABOUT SUSAN FOLLETT

IN BRIEF

Susan Follett is an advocate for using stories to increase awareness of history and dismantle the stereotypes that divide us.

Having grown up in the shadow and silence of Jim Crow—unaware of the March from Selma scarcely 100 miles from her hometown Meridian, Mississippi, where three civil rights workers disappeared during Freedom Summer—she set out to examine and reimagine the times. The Fog Machine was published in 2014 in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer.

As author and public speaker, Susan shares Civil Rights Movement history and her journey of discovery. Her “Stories from Civil Rights History, Then and Now” events help classrooms and communities connect history to today. Her work explores prejudice and what enables change. She lives in St. Paul, MN.

EXTENDED BIO

Susan Follett is author, literary activist, and producer of “Stories from Civil Rights History, Then and Now” events for classrooms, communities, and book groups. She is the recipient of a McKnight Artist Fellowship in creative prose.

Susan grew up in the epicenter of the Civil Rights Movement: Mississippi in the sixties. When the first African American stepped into Highland Park’s public pool in Meridian on the same day Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon, she was attending summer journalism camp at the University of Mississippi. Her graduating class at Meridian/Harris High School was the first under federally mandated desegregation.

After earning a master’s degree in computer science from Mississippi State University, she left Mississippi. Her career in corporate technology management began at the height of the women’s movement and took her to the Twin Cities of Minnesota, the Bay Area of California, and Portland, Oregon.

A television documentary Ms. Follett saw as a young adult, about the March from Selma to Montgomery, haunted her, raising questions about the time and place in which she grew up: Why hadn’t she known the history? And what might be different if she had?

Ultimately, she turned an adult eye on her childhood during Jim Crow. Interviewing Civil Rights Movement veterans, historians, and Mississippi residents. Discovering divides not unlike those across the U.S. today.

The Fog Machine, her first book, is the result of that research and reflection. An historical novel that explores universal themes of prejudice and what enables change.

Susan advocates for using the power of story to engage in learning and critically thinking about our full, authentic history. She cherishes each individual reader and takes particular delight in having The Fog Machine discussed in book groups, classrooms, and community reads. She is available for events in the Twin Cities, MN area or via ZOOM or FaceTime. Contact her here.

Susan is at work on her next book, which will once again tackle divides, linking another historic era in Mississippi to today’s American challenges. She lives in St. Paul, MN with her husband.

Lucky Sky Press Q&A:

A Conversation with Susan Follett

Commemorative Road Sign: Selma to Montgomery Marches

“Selma to Montgomery marches – historic route” by Markuskun, October 2007, Public Domain.

Q: You were educated in computer science and spent more than twenty years working in information technology. How then did you come to write an historical novel?

A: On April 26, 1984, my roof was literally—and figuratively—ripped from my house when an F-3 tornado struck my suburban Minnesota neighborhood. That night, staying with a friend and unable to sleep, I turned on the television and happened upon a documentary about the March from Selma to Montgomery. I watched, riveted, as unfamiliar history unfolded—events that took place scarcely 100 miles from where I grew up in Meridian, MS. Though my house would be relatively easily restored to its original condition, I would be forever changed. Though it would not happen for years, I would be drawn home on a journey of discovery that would give birth to a novel.

Bloody Sunday: March 7, 1965

Alabama Police Attack Selma-to-Montgomery Marchers

“Bloody Sunday,” 1965, Public Domain.

Q: What was the March from Selma to Montgomery, and what about it captured your interest?

A: On March 7, 1965—a day now known as “Bloody Sunday”—600 people headed east out of Selma, Alabama on U.S. Route 80. Marching for the right to vote, they reached the Edmund Pettus Bridge six blocks away before state and local lawmen attacked them with billy clubs and tear gas. They would try again twice, reaching the capitol 25,000 strong on March 21. Less than five months later, President Johnson would sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The images I saw on the TV screen—dangerous, brutal, and arbitrary—somehow combined with images of the tornado to heighten my reaction. Overarching the shock and shame was confusion. Though my focus remained on my career for years after seeing the documentary, I never let go of these questions: Why hadn’t I known about it? And what might be different if I had?

Q: How is it that this history was unfamiliar to you?

A: That must sound surprising! Especially since I often say that I grew up in the epicenter of the Civil Rights Movement—Mississippi in the 1960s.

One thing that got in the way of my knowing about the Civil Rights Movement as it was happening was the relative unavailability of information as compared to today. Remember that the Internet did not exist back then. While television stations today broadcast 24x7, back then many signed off after the ten o’clock news. Especially in less populated areas, TV viewers had access to a local station rather than multiple national networks. And history books did not yet cover the unfolding action.

That said, there are similarities between then and now. Key among those are people who distort or withhold information for their own purposes. Technological and commercial differences aside, being unfamiliar with our history is a problem that plagues us today as it did then.

Q: How did you familiarize yourself with this history?

A: By the time I began to actively consider why I hadn’t known much about the Civil Rights Movement, several decades had elapsed. On the one hand, books had been written. On the other hand, participants in the Civil Rights Movement were aging, and many had passed away during or since the movement. I wanted, as much as possible, to get first-hand accounts.

I conducted my first interview in 2000. Meridian civil rights attorney Bill Ready Sr. painted a picture of the time and place in which I grew up. One TV station. One newspaper. Each owned by the same man. Parents, white and black, intent on protecting their children from harsh realities.

As the instigating questions led to many more, I began to read—dozens of oral histories captured as part of the University of Southern Mississippi’s Civil Rights Documentation Project. And I wrote—what I now refer to as “my essay about the story I wanted to write.”

In 2007, I began interviewing in earnest, across the movements: civil rights, anti-Vietnam War, and women’s rights.

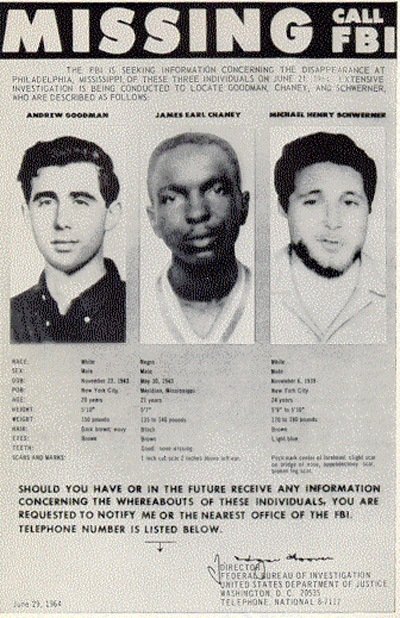

June 29, 1964 FBI Poster For Missing Civil Rights Workers: Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner

“FBI Poster of Missing Civil Rights Workers” was taken as part of the official duties of a Federal Bureau of Investigation employee. As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the Public Domain.

Ben Chaney, voter rights activist whose brother James was murdered along with Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman outside Philadelphia, MS in the summer of 1964.

Photo by Warren K. Leffler, August 22, 1964

Fannie Lou Hamer: August 1964 Democratic National Convention

Reverend Ed King, native white Mississippi Methodist minister who, with Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, Aaron Henry, and others, attended the 1964 Democratic National Convention representing the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. They tried, and failed, to unseat the Dixiecrats, the all-white state Democratic Party delegation; yet MFDP opened many Americans’ eyes to voter discrimination.

Heather Tobis Booth, an important contributor to the early women’s movement in Chicago and, like my character Zach Bernstein, a Freedom Summer volunteer from the University of Chicago.

Q: The Fog Machine is told from three perspectives: a twelve-year-old white girl, a young Black woman who leaves Mississippi to work as a live-in domestic in Chicago, and a University of Chicago student who hails from New York. These three characters also practice three different religions. They are, respectively, Catholic, Baptist, and Jewish. What presented the biggest learning curve here?

A: Well, the learning curves came at me like balls in a batting cage. And, of course, not the least of these was educating myself to be able to write authentically about someone of a race other than my own. But religions, with their diverse beliefs, foods, and cultures, also required a lot of learning. Like Joan Barnes, I grew up Catholic in predominantly Baptist Mississippi. So, Judaism involved the most religious research for me.

As Zach’s character became an integral part of my story, I needed to educate myself about Judaism—from the food, to worship practices, to beliefs. I recalled how, in 1968, Temple Beth Israel in Meridian, MS was bombed, and rumors spread labeling the act as Klan retaliation against civil rights sympathizers. Knowing of the role of reform Jews in the Civil Rights Movement, I connected with reform rabbis and congregants in Chicago.

I was informed by people too numerous to mention but am especially indebted to Chicago Sinai Congregation, Harriet Hausman, Rabbi Robert J. Marx, Chuck Mervis, and Rabbi Paul Saiger. Chuck Mervis graciously shared sermons written by his late father, Rabbi Leonard Mervis, around the time when Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Mrs. Hausman and Rabbi Marx participated in the March on D.C. and brought that particular moment in history to life for me. Rabbi Marx was also with Dr. King in Selma.

Q: How did you know if you were “getting it right?”

A: In 2010 I shared my developing manuscript with those I’d interviewed and with new people I’d begun to meet: educators, movement figures, and book groups.

Vickie Malone, social studies teacher who piloted civil rights education at Mississippi’s McComb High School. Ms. Malone’s local cultures class inspired Mississippi’s K-12 public school mandated civil rights education curriculum. Mississippi was the first state in the U.S. to issue such a mandate.

Photo by Melissa Follett, Meridian 5: MHS Graduation Portraits

Faye Inge, former language arts teacher and Freedom School student who is one of the “Meridian 5.” These five African American women desegregated Meridian High in 1965, well before Mississippi finally complied with federally mandated desegregation in January 1970.

May 14, 1961: Freedom Riders watch bus burn just outside of Anniston, Alabama

Image made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Janie McKinney who, in 1961 as a twelve-year-old white girl, gave aid when one of the Freedom Riders’ buses was attacked outside her Anniston, AL home. Her story in the PBS American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders” caused my heart to ache for the schism she must have felt—needing to honor her faith and basic humanity, fearing what might happen to her father and family’s livelihood, terrorized by her own fear and the overwhelming circumstances surrounding her.

The first book group to take up my pre-published manuscript was Seattle’s The BookClub. Jackie Roberts, member and co-founder of Seattle’s Interracial Dialogue Series, was my gracious host.

Q: And were you?

A: At this point, no! Reader feedback suggested that my education hadn’t yet gone deep enough, that I wasn’t yet challenging enough of my own long-held biases. Also, though Freedom Summer is the pivotal element in my story, it was underdeveloped back then. Uncovering and challenging bias and fleshing out the summer of 1964 in Mississippi required more research.

With permission from: Mark Levy Collection, Queens College/CUNY, Civil Rights Archive

Gail Falk (front), teaching at Meridian Freedom School, 1964

Montgomery Institute Senior Fellow Dr. Bill Scaggs, another reviewer, introduced me to Gail Falk, who taught at the Meridian Freedom School 1964-65. Gail became both mentor and muse, informing and enlightening me about the Mississippi Summer Project in Meridian in 1964 and connecting me with others, including Mark Levy, who was the principal of the 1964 Meridian Freedom School. Gail and Mark provoked me to dig deeper to convey the complex mix of emotions experienced during that time.

Q: You’ve said that The Fog Machine is about prejudice and what enables us to change. How important is that in your book?

A: It’s the most important thing to me! My passion lies in tackling complexities such as Gail, Mark, and many others opened my eyes about. The themes that most resonate for me are those of everyday heroism, prejudice, and personal change.

In writing about those themes, I strive to portray prejudice as a shared human challenge. Not a “Mississippi thing” or “southern problem.” Rather, a learned behavior that can be unlearned. By opening ourselves to getting to know—on an individual basis—people we view as different than ourselves. As Martin Luther King Jr. taught: “Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that.”

And so, I develop my characters with differing degrees of prejudice. Never to excuse or mitigate. Always to enlighten about prejudice and what enables us to change.

Q: Did you set out to write a novel? Or were you really just focused on those big “what ifs:” Why hadn’t you known more about the time in which you grew up? And what might have been different if you had?

A: My initial objective was to answer those two questions for myself. As I moved through the journey of discovery, I realized I was gathering precious stories that could be knit together and shared.

Reflecting Pool: 1963 March on Washington

Each time I think about the people I’ve been honored to interact with during the writing of The Fog Machine, I am awestruck and filled with gratitude. I’ve tried to capture history from aging history makers and present it through relationships. One example is the scene at the Reflecting Pool during the March on D.C.

“Seventy-five years now I been living in this country,” said the old Negro in a voice that rang out like Mahalia Jackson’s. “But today’s the one I become a man.”

— From a true story, shared by Rabbi Robert J. Marx

I also realized I had learned so much of the history of my childhood—and even why it was unfamiliar to me—but I still could not answer what might have been different had I been more aware. And that’s where the power of fiction took hold of me, with its potential for “what ifs,” for imagining. My characters C.J. Evans, Joan Barnes, and Zach Bernstein emerged and helped me imagine.

Q: This journey of discovery that led to The Fog Machine has been a long one, hasn’t it? What’s next then?

A: Indeed, it has been a long journey! Capturing history, lest we forget or never even know it, and exploring what enables change in human beings. I’ve concluded this: a complex interaction of family, culture, society, politics, personality, religion, what we value, what we fear, and who we meet determines both what prejudice we feel and our ability to change.

I hope my novel The Fog Machine will find its way into the hands of countless more book groups, individual readers, students, and teachers where it can continue to entertain as well as inform. I cherish each individual reader and take particular delight in having The Fog Machine discussed in groups.

At the same time, I cannot help but be alarmed by the divides that plague America, so many years now beyond the Civil Rights Movement. I’m at work on my next book, which will once again tackle divides, linking another historic era in Mississippi to today’s American challenges.